CES 2024 – Consuming an Ersatz Singularity

It’s hard to be a techno-optimist in Las Vegas. How does anyone look at slot machine zombies or smartphone-guided hookers, and think “gadgetry will save the human race”? Here and there, you’ll see some whiskey-bent hombre weave across the casino carpet, reduced to nothing but two eyeballs and a brain stem. Parents even bring their kids out here, preparing them for a life of neon hypnosis and impulsive consumption. Everywhere you look, everyone is going nowhere fast.

It’s hard to be a techno-optimist in Las Vegas. How does anyone look at slot machine zombies or smartphone-guided hookers, and think “gadgetry will save the human race”? Here and there, you’ll see some whiskey-bent hombre weave across the casino carpet, reduced to nothing but two eyeballs and a brain stem. Parents even bring their kids out here, preparing them for a life of neon hypnosis and impulsive consumption. Everywhere you look, everyone is going nowhere fast.

The Vegas Strip is a parody of human civilization—from our glorious beginning to our hardwired end. Walled in on all sides by desert mountains, you can stumble from a simulation of ancient Egypt at the Luxor to imperial Rome at Caesar’s Palace, tossing fiat currency into the void along the way. Then it’s onward to medieval Europe at Excalibur, cosmopolitan France at Paris Las Vegas, and an urban American rollercoaster at the New York-New York casino.

Presently, one side of the Luxor’s pyramid is a giant Dorito chip ad. There’s something poetic in that image.

If you don’t collapse in late modernity, you might end up in a global technodrome at the Sphere. The newly constructed venue is basically a giant LED eyeball outside and a neurotech cage for eyeballs inside. It’s a temple to transhuman illusions (check back this weekend for my full review). In fact, every tourist attraction in Vegas is designed to capture the eye, bombard its rods and cones with dazzling lights, and imprison the soul in desire. So the city is a fitting milieu for the annual Consumer Electronics Show.

Last week, over 130 thousand nerds gathered at venues all over Las Vegas to browse transparent TV sets, puppy-eyed social robots, smart home spyware appliances, dubious autonomous vehicles, and endless virtual reality goggles. The crowd was a mix of tech heads, wealthy investors, and Vegas tens paid to flash their bright smiles at display booths.

CES 2024 was a cross between a science fair and a funny farm, powered by money to burn. There were neuromorphic computer processors and a massive robotic backhoe. There were autonomous lawnmowers and an AI-guided baby stroller. There were battery-powered, genderfluid Tron bikes and Chinese electric cars that are basically smartphones on wheels. There was an Internet of Bodies WiFi system that transmits data through your bodily fluids and an app called Adam to secure your personal data after you die. (To my surprise, the CEO of this afterlife company, Revenant, told me he believes in an eternal soul.)

Most of these gadgets will wind up in the dustbin of imaginary technocracies. However, a few will ride into the Future by way of consumer choice, corporate saturation, or government mandate.

by way of consumer choice, corporate saturation, or government mandate.

Pretty much everyone I met was friendly and well-intentioned. If anything, I was the biggest jerk in the room. It would be easier to condemn this techno-dystopia if its creators were all evil. But by and large, these are innovators toiling away to make life better for other people—or at least for people who share their aesthetics. They’re just having fun. It’s not their fault so many of us detest the end products.

Let me take you on a brief tour of imagined futures.

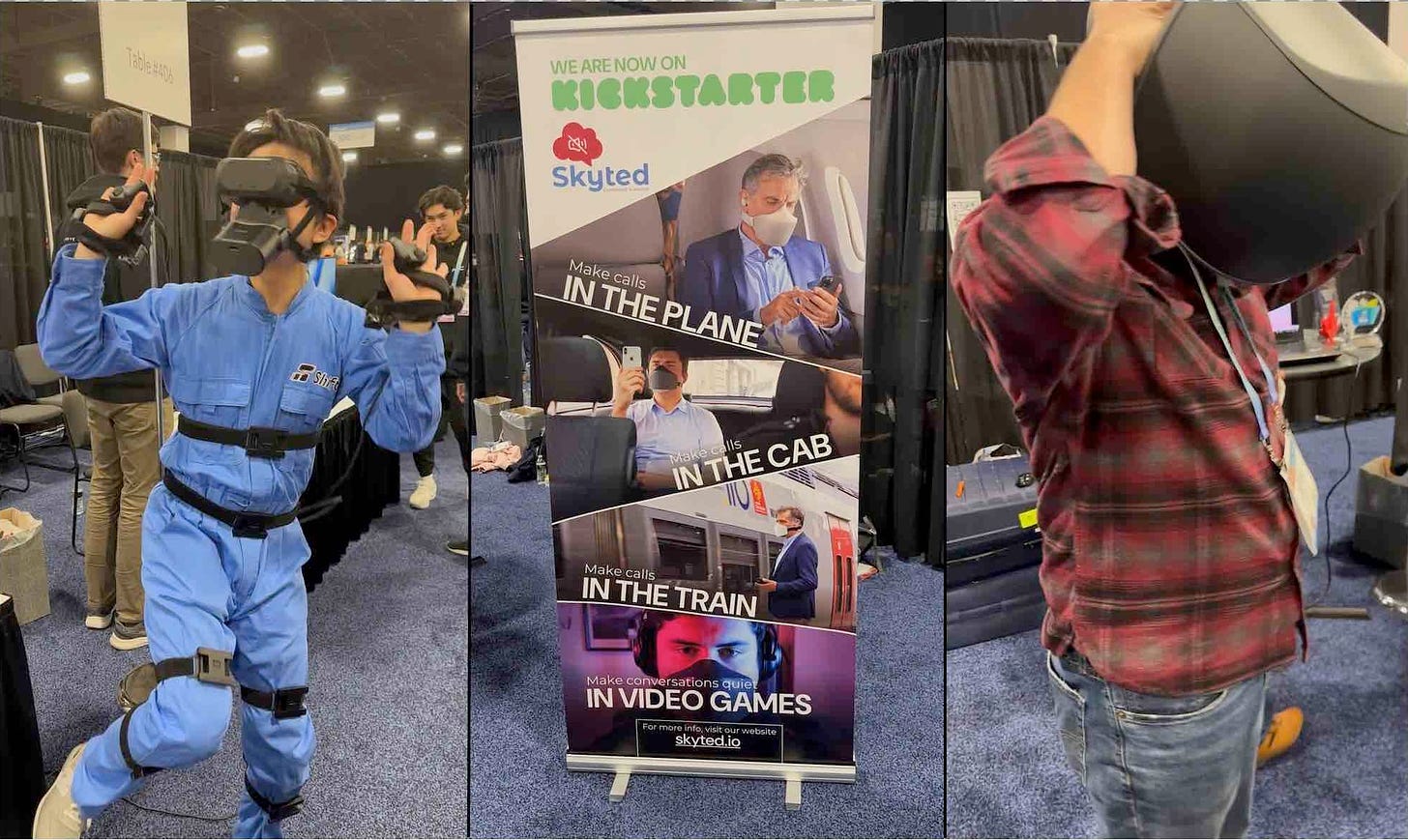

The Skyted noise-blocking microphone mask looks like something a fighter pilot would wear. But it’s made for chatty commuters and coffee shop patrons—or maybe secret agents and drug dealers—who don’t want their phone conversations overheard.

On the one hand, pointless face masks are super annoying. On the other, people who yak on their phones in public are twice as annoying. Until we can abolish speakerphones, this mask may be a tolerable compromise. Seriously, I think we should mandate them along with earbuds.

Volume up? Cover up!

Not to be outdone, the Shiftall crew combined this phone-muzzle tech with virtual reality goggles. When I came upon their demo at the media sneak peek, a little Asian man in overalls was dancing around with his eyes and mouth covered. He looked like a borged out Ghostbuster who’d been shoved into Thunder Dome. On a nearby screen, his virtual avatar was an anime waifu wearing pigtails.

The scene was somewhere between transgender and transhuman. It looked like some sort of psychological torture. In the Metaverse 2.0, no one can hear you scream.

I was reminded of the World Economic Forum’s concept of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which Klaus Schwab defines as “the convergence of the physical, digital, and biological worlds.” Indeed, one VR company at CES, MetaVu, displayed a slogan promising the same: “Digital Twin: Convergence of the Virtual and the Real World.”

Across the metaverse area of the Las Vegas Convention Center, the digital invaded the physical through holographic LED video walls and 3D phantoms hovering inside crystal balls. Meanwhile, attendees escaped the physical world into virtual reality goggles. They donned all sorts of haptic gloves and bracelets and vests. They shot bad guys with machine guns. They grasped Platonic solids in virtual space. They played drum n’ bass on airborne sequencers.

The VRLCO virtual reality system looked like it had a brain-computer interface attached. A clawed device is locked onto the player’s head like a parasitic crab. Apparently, it just holds the goggles on—for now. But neurotech companies like NextMind and OpenBCI have already developed wearable brain scanners for VR applications. You’ll soon see them for sale everywhere.

As consumer BCIs become more common, corporations won’t have to wonder if their game-addicted customers are getting brain damage. They can watch the decay in real time.

There were plenty of actual brain interfaces on display at CES—for the impaired and curious alike.

Laina Emmanuel at BrainSight AI told me about her company’s quest to map cognitive function. Their systems track the attention network, executive function, and the structural connections that make humans go. The AI can analyze neural data gathered from either non-invasive scanners or implanted brain-computer interfaces. The end result is a “virtual twin” of a patient’s gray matter. This digital double can be used to assist neurosurgery, for early dementia diagnosis, and to help treat various psychiatric disorders.

BrainSight AI is used in over twenty hospitals in India, and a growing number of American facilities, so obviously they aim to heal. But what about the transhuman goal of enhancement?

“We do get a lot of requests from people coming to us saying, ‘Hey, connectomics, can you map my brain—which I can then use to stimulate and become a superhuman?’ But we’ve been very focused on medical devices,” Emmanuel assured me. “We’ve not really gone into the more esoteric cases.”

Who are these prospective “superhumans”? High rollers?

“Yes, mostly wealthy people who are well settled and now they are thinking of the next new thing,” she told me. “Like at CES, or at various conferences, you have people come in and be like “Oh, this is so cool! We would love to know how to enhance our language function or enhance our ability to concentrate.’”

People often ask what kind of person would willingly take a trode to the dome. Well, look no further than the technophiles at CES. Many are begging for it.

If the metaverse is here to cover our eyeballs with digital worlds, then the Internet of Things and the Internet of Bodies are set to cover our physical world with digital eyeballs. Our homes are to be watched by AI-powered devices, as are our outward behaviors, our personal interests, and our social connections. Likewise, our bodies are to be watched by wearables or even implants—our heart rates and our emotional states, our digestion and our sexual arousal. We are to become data.

Companies like Body Log, SensePlus, and SmartSound AI can measure every process in your brain and body like barely visible, but overly curious nurses. For those who want to continue their bloodline into this dystopian web, products like Sperm Tester are there to make sure your boys are swimming straight. The Louise app—named after the first baby conceived through in vitro fertilization in 1978—was created to identify the causes of infertility in the hopes of finding an appropriate workaround. Once your baby is born, companies like HubDIC can provide an IoB crib outfitted with a moving camera to monitor the infant’s every move and whimper.

But what if you can’t bear to bring a new life into this digitized world? Well, you can always augment your 5-digit relief with the Handy—a mechanical “interactive masturbator for penis-owners” that’s interoperable with virtual reality. Once you’ve given yourself over to its grip, the friction of real life just melts away.

Not everyone at CES was starry-eyed and primed for submission, though. As I meandered around, the technologist Richard Crisp picked me out of the crowd. He was there to promote his memory chip company, Etron. As it happens, he’s an avid War Room viewer. After going over the positive uses of digital tech, I asked him what the downsides might be.

“My biggest fear is we’re creating a digital jail,” he told me. “I worry a lot about that. So long as the technology’s used to improve life, to improve safety, to help prevent problems—I like it.”

But the dangers?

“Full time surveillance all the time, everywhere you go,” he replied. “Tracking everything. Digital cash—every transaction you make. That stuff is abusive, in my opinion.” Like central bank digital currencies? “They’re coming whether you like it or not. And I don’t want anything to do with it.”

Nor do I. Yet here we are.

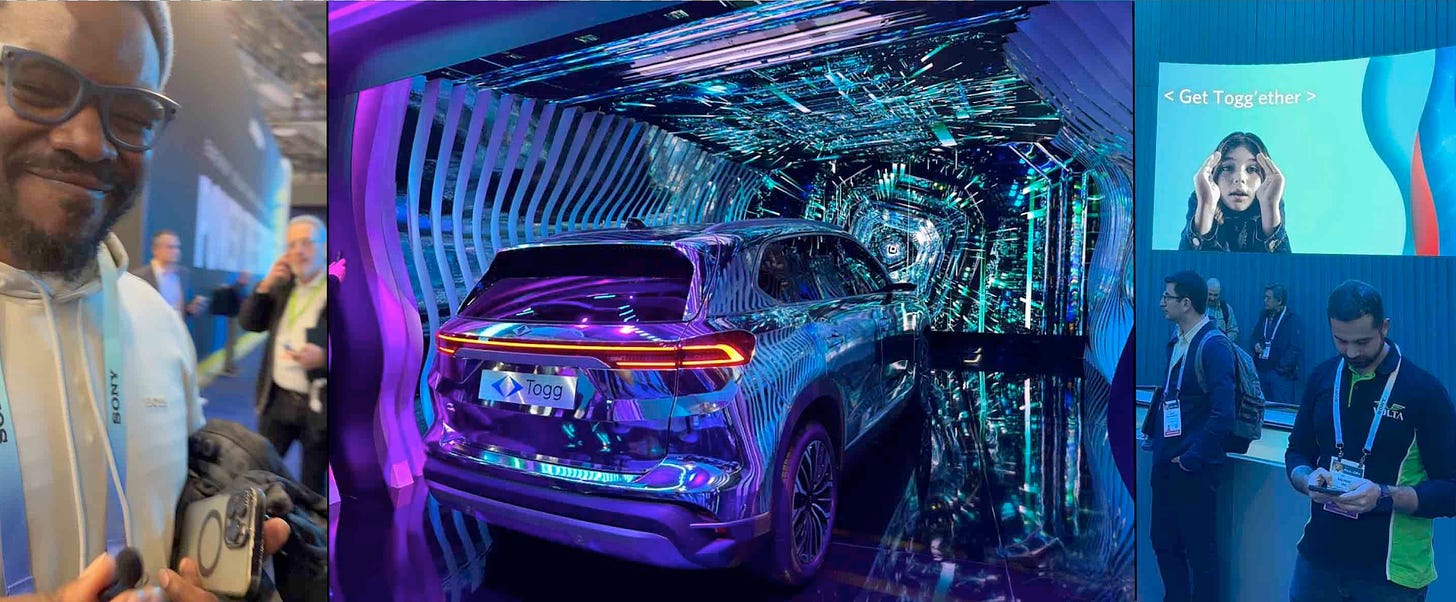

Keeping up with the latest trends, the Togg car company created an electric SUV that also functions as a smart device. Cameras watch your outward behaviors. Various sensors measure your body’s internal states. The idea is to bring the virtual and real worlds “Togg’ether.” (Painful, I know.)

Togg had a virtual reality exhibit at CES. You get into their SUV inside a VR tunnel, and the generative AI tailors its output to your biometric input. It’s more gimmick than technical wizardry, but I had to give it a go. As it happened, I took the ride with Ehi Binitie—creator of Iyoba Land, an African VR platform. Ehi is originally from Nigeria. He now lives in Atlanta.

Being a half-assed journalist, I attempted to record the experience on my smartphone, but failed to switch the camera to video. All I got was a single blurry photo. Fortunately, Ehi is a professional cyborg. He caught the whole thing on his Meta smart glasses. Like millions of people, he records most of his life on them, and has since he got his first pair of Snapchat glasses nine years ago.

After the ride, I asked why he’d submit to full-time self-surveillance. For him, feeding your entire life into artificial intelligence is something like a religious duty—a quest for deeper meaning and digital immortality. “AI is gonna be curating our lives in the future,” he insisted. I told him I’d rather God remember and let the physical world forget. He said I was doomed to be left behind.

“It’s kind of like cars and horses. If you don’t get with the cars, you have to be in the stable. You have to be stuck with that technology,” he said. “You know, evolution has always been the majority of the people. So a few people may drop off, and we will still look to you for encouragement and to keep us centered. But you won’t be the majority of the people. That’s just civilization.”

As we bantered about kids these days getting soft and weak, Ehi told me a story that could be a parable for the entire CES scene. As a boy, he went to a Nigerian boarding school. Every day, he had to lug buckets of water back from the river. “It was something I dreaded.”

Then a few years ago, he returned to Nigeria to see his father in the hospital. One day, the water system failed and the staff had no idea what to do. Naturally, Ehi grabbed a bucket and started hauling water back from the river. At first the hospital staff mocked him. Then they realized how helpless they’d become.

“People get dependent on technology,” Ehi mused, “they get dependent on water coming out of the pipes. When it doesn’t work, they just give up, and say ‘There’s no water. There’s nothing I can do.’ While technology makes life easier—and better—you still have to remember your old school ways of doing things.”

That’s not happening, though. It’s like humanity climbed up a cliff face and forgot how to climb back down.

You know, Las Vegas creeps me out for a lot of reasons. But the biggest is that the city rises out of a lifeless desert valley. If they lost water for even a few days, the neon lights would flicker out and the lizard-like inhabitants would be drinking each other’s blood. The trees and grass would wither. Scorpions and sidewinders would pick over the ruins.

For anyone paying attention, CES is a microcosm of humanity’s accelerating tech dependency. Our culture is being automated. Our bodies and brains are being digitized. How long before what comes out the other end is no longer recognizable as human? And how long can such a creature survive?

DARK ÆON is now for sale here (BookShop), here (Barnes & Noble), or here (Amazon)

If you are Bitcoin savvy and like a good discount, pick up a copy here at Canonic.xyz

The post CES 2024 – Consuming an Ersatz Singularity appeared first on Stephen K Bannon’s War Room.